Authors Daniela Müller‑Eie and Ioannis Kosmidis published an article in the European Transport Research Review named “Sustainable mobility in smart cities: a document study of mobility initiatives of mid‑sized Nordic smart cities”.

The article provides an a-up to date review on this issue. Here are some of the key issues.

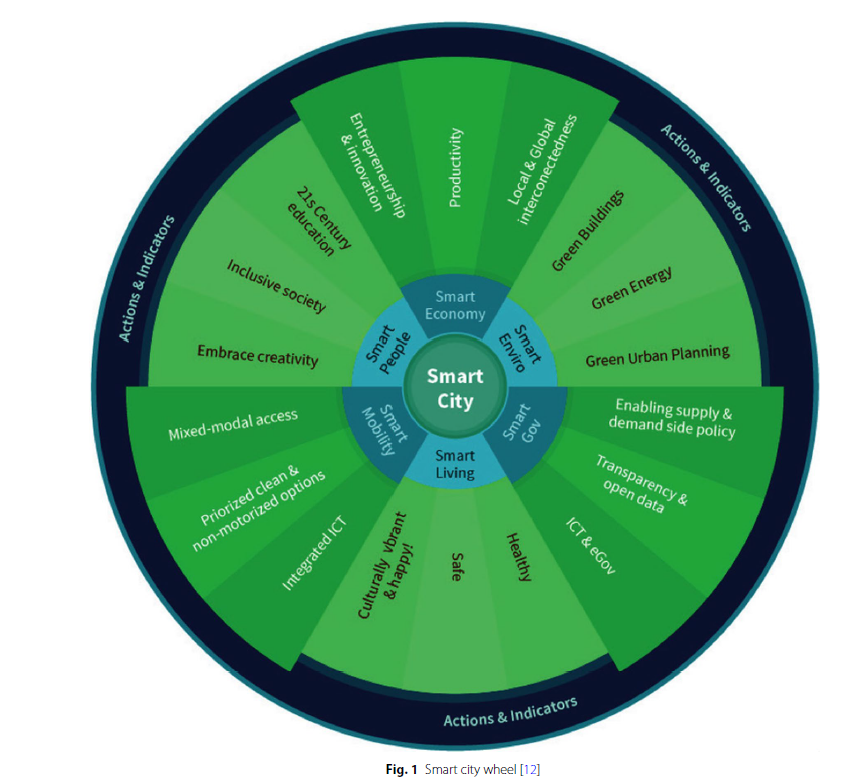

The smart city concept is being viewed as part of the urban future, integrating technological advances, multi-sectoral collaboration, and innovative open markets with strategic goals and ambitions to achieve sustainable urban development.

Smart mobility is considered a vital element of the smart city, given that urban transport systems should become more efficient and sustainable. The authors raised the question: how sustainable is smart mobility?

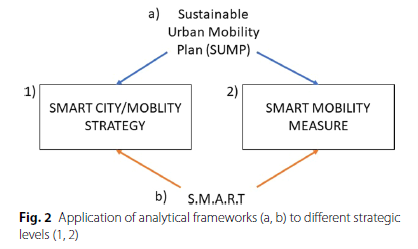

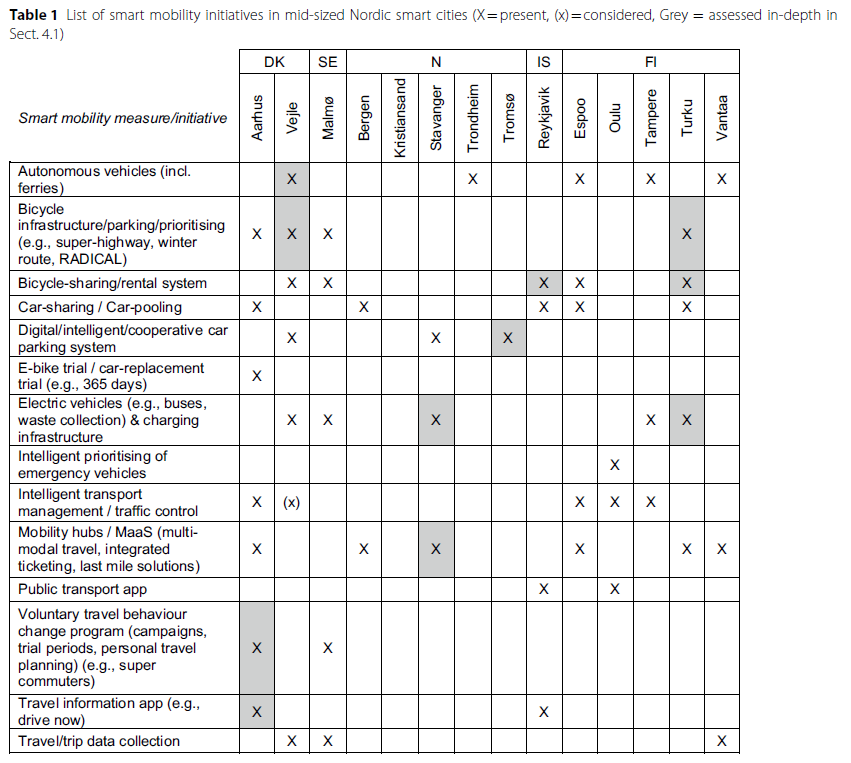

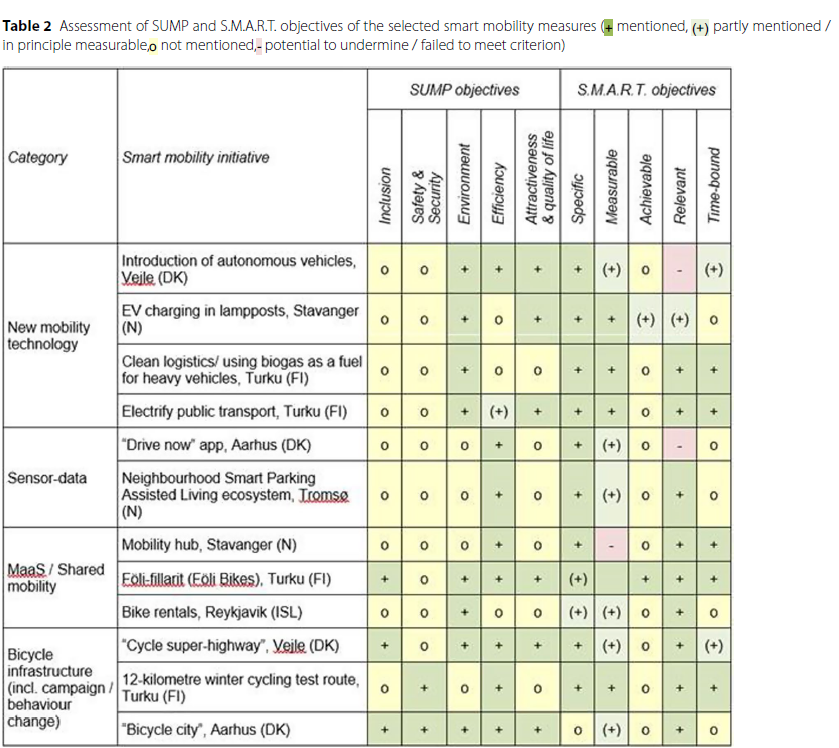

The study’s objective is to review smart mobility strategies and concrete measures of Nordic smart cities and to evaluate the detected smart mobility measures in terms of feasibility and manageability, as well as contribution to sustainable mobility goals. Smart mobility is often discussed on two levels: (1) the strategic level and (2) implemented measures. Therefore, both the strategic goals and mobility measures were evaluated separately during the study. To do this, researchers used a two-fold methodological approach, consisting of two analytical frameworks: a) the objectives of Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMP), and b) the S.M.A.R.T. objectives. The first set of criteria directly examines sustainable mobility, i.e., the overlap between the smart mobility strategies and initiatives of a city with the objectives of the EU’s Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP). The latter assesses the feasibility and accountability of goals with the help of the S.M.A.R.T. framework from management disciplines.

Analysis

According to the European Commission, smart cities are “cities using technological solutions to improve the management and efficiency of the urban environment” but they also go “beyond the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) for resource use and less emissions”.

Smart cities have been characterized through tools such as smart technology, Internet of Things (IoT), open data, public–private collaboration, competition, and user involvement, claiming that automatically collected data and inter-urban competition can lead to societal benefits, comfort, and better allocation of resources. Important stakeholders in the smart city are the urban government, planners, politicians, technological consultancy companies, knowledge organizations, and inhabitants

The objectives of smart mobility include mixed modal access, prioritized clean and non-motorized options, as well as the reduction of traffic congestion, transfer costs, air, and noise pollution, improved transfer speed and increased safety.

All measures using technological advances (i.e., AV, EV, biofuel, E-PT) aim at reduced environmental impact, by reducing energy consumption and emission. The same is true for bicycle sharing or rental systems and improved bicycle infrastructure.

This shows that the selected smart mobility measures have a stronger focus on environmental impact, efficiency, health and well-being. The social sustainability aspects, however, seem somewhat neglected or at least under-communicated. While these findings are generally encouraging in terms of smart mobility measures addressing environmental aspects, the authors stressed that this indicates a narrow understanding of sustainable urban mobility with environmental and economic aspects prioritized over social aspects.

Likewise, it is theoretically possible to achieve all targets. However, none of the reviewed measures has a concrete benchmark for when the project would be considered a success (or failure). The research pointed out that his lack of concrete goal posting again makes it difficult to assess smart mobility initiatives.

The relevance of the introduced smart mobility measures is assessed on whether the measure itself or its goals and outcomes are in line with or in conflict with other goals. While most of the studied smart mobility initiatives are in line with, for instance, carbon neutrality or the promotion of public and active travel, introducing AVs, EVs and making driving and parking more effective can conflict with the goal of making sustainable transport modes more attractive and reducing car dependency. The study indicated that such goal conflicts can generate suboptimal results, particularly if the goals have varying degrees of priority, support, and acceptance among policymakers and the population.

Thus, the reviewed smart mobility measures seem to be well-defined in terms of targeting specific goals and are relevant and well-aligned with the aims of other smart mobility solutions. However, they lack measure ability, success benchmarks for achievability, and specific timeframes for goal achievement. This is worrisome as it can result in measures being introduced without plans of effect evaluation and therefore little sense of accountability.

Not assessing the effects of the mobility measures, results in a low degree of measurability and accountability.

Conclusions

The study pointed out that the smart city and its interventions are technology-driven’, meaning they build on the belief that increased efficiency and market opportunities are the way toward sustainability rather than reduced consumption.

Within this, there is sometimes a focus on technological aspects without explicitly mentioning the added value compared to conventional or passive solutions, such as when using data for improving car flow or promoting EVs, compared to creating physical infrastructure to make the bike more attractive.

This begs the question, whether the smart city agenda makes us overlook alternative ways towards more sustainable urban transport that lay outside the scope of smart mobility (i.e., increased use of ICT, vehicle efficiency, technology), but rather revolve around reduced transport and behavior change. This begs the question of whether the focus on smart mobility solutions deters cities from conventional transport measures that may be equally or more cost-effective and efficient in achieving environmental goals. It also seems that the social aspects of sustainable urban mobility, such as traffic safety, social inclusion, attractiveness, and quality of urban life receive less focus and are only mentioned rarely as explicit targets of smart mobility measures.

When investigating whether smart mobility measures are well-designed to achieve urban mobility goals with the help of the S.M.A.R.T. framework, the authors founded that most measures have specific goals or targets and are relevant to contributing sustainable urban mobility through aiming at the improvement of travel quality, reduction of environmental impact and an increase in public health. However, some measures also display conflicting goals, for instance, when making car use more efficient as opposed to promoting green travel.

A general challenge is that many smart mobility projects are not well described and often seem to be put in place because they are smart and possible but may lack explicit justification for implementation.

Another pressing issue is that smart mobility projects often lack any explicit aim at measuring or benchmarking effects within a certain time frame. This is concerning, as it makes goal assessment difficult. Ideally, it should be possible to assess effects and base further policy decisions on accountable and verifiable data, whenever projects are funded publicly. However, this is also true for conventional transport projects.

In the field of transport and mobility, it is widely acknowledged that sustainable urban mobility must cater towards more active and public travel and less focus on private car use. In smart city practice, however, there are examples where technological transport solutions are implemented without clear goals of improving urban mobility. While part of the solution may lay in smart technology, co-creation, education, or governance, it is also possible that other solutions may be more efficient or cost-effective that are currently not given enough attention due to the strong focus on smart cities and technological development. For smart mobility initiatives to be relevant over time, they must become more measurable and accountable, not least in their contribution to sustainable urban mobility.

The authors understanded this way of reviewing smart mobility measures, and transport measures in general, as a positive contribution in two ways. Firstly, it does not only evaluate smart city and mobility measures in themselves but rather in their contribution to sustainable development. It is important to commit smart cities to work coherently towards sustainable urban futures. Secondly, such an assessment can pinpoint shortcomings in policymaking by requiring policymakers to reliably deliver on set objectives as well as overarching goals of urban sustainability.