Researchers Åsa Hult and Lisa Perjo from the Sustainable Society Unit, IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, Sweden, and Göran Smith from the Mobility and Systems, RISE Research Institutes of, Sweden (also from Department of Regional Development, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden and Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, University of Sydney, Australia), published an article in Sustainability on 10 September 2021, regarding shared mobility in rural contexts. The article provides an a-up to date review on this issue. Here there are some of the key issues.

Rural contexts are characterized by low population densities and long distances between societal functions such as schools, shops, and healthcare facilities. These characteristics make it difficult for public transport authorities (PTAs) to provide a level of service that is both satisfactory for rural dwellers and financially reasonable for taxpayers. Consequently, rural populations are oftentimes more dependent on car travel. For instance, according to the most recent national travel behavior survey in Sweden, people in small towns and rural municipalities use cars for about 76% of their daily traveled kilometers, while the corresponding number for people in large cities and in municipalities near large cities is 48%.

One consequence of the high car dependency within rural transport systems is that many are forced into car ownership. In other words, many rural dwellers own and use cars even though they would rather not. However, since cars are expensive and require physical and cognitive abilities, this option is not available for all, especially not for children, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

Thus, the study establish that although the share of the population that is exposed to car deprivation in rural areas is lower than in cities, the perceived consequences for those who cannot get access to or drive cars are more severe; transport poverty is more likely to be a source of social exclusion on the countryside.

The Problem: Transport Poverty in Rural Areas

Transport poverty is a broad, overarching notion that encompasses mobility poverty (lack of transport options), accessibility poverty (difficulty of reaching certain key activities), transport affordability (lack of resources to afford available transport options), and exposure to negative transport externalities. Hence, an individual can be said to be transport poor if at least one of the following conditions apply:

- There is no transport option available suited to the individual’s physical condition and capabilities

- The available options do not reach destinations where the individual can fulfil daily activity needs

- The money spent on transport leaves the household with a residual income below the poverty line

- The individual needs to spend an excessive amount of time travelling to fulfil daily activity needs

- The travel conditions are dangerous, unsafe, or unhealthy for the individual

The Proposed Solution: Mobility as a Service

“The vision is to see the whole transport sector as a cooperative, interconnected ecosystem, providing services reflecting the needs of customers and seamlessly combining different transport means, such as private vehicles, public and collective transport (bus, metro, light rail, car sharing), biking and walking”. In practice, this means offering a new digital service layer, which provides users with a single point of access for finding, booking, and paying for mobility services.

Although MaaS arguably still mostly exists in PowerPoint presentations and strategy documents, a few services are available to the public, especially in European cities. These include Jelbi in Berlin (jelbi.de), Whim in Helsinki, and Yumuv in Zürich, Basel, and Bern. However, pilot projects excluded, there are few examples of MaaS services that address the travel needs of rural dwellers.

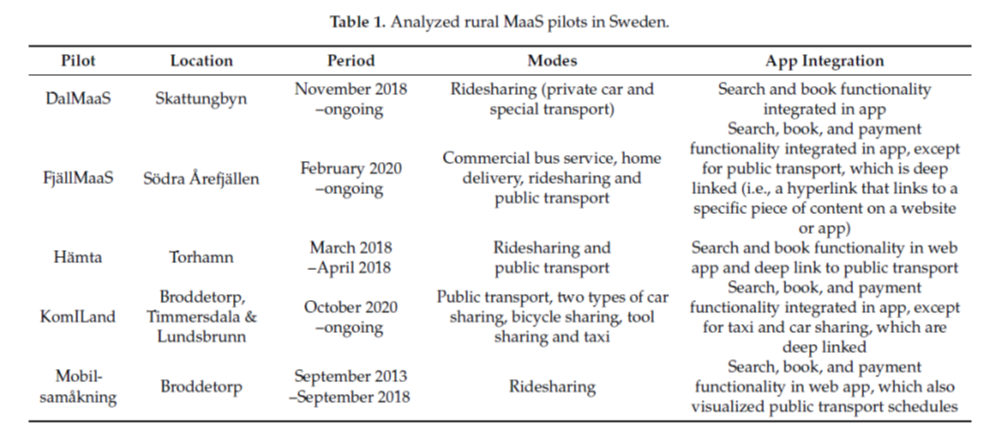

The analysis in the article covers pilots of shared mobility and MaaS in rural areas of Sweden.

Future Roles and Activities

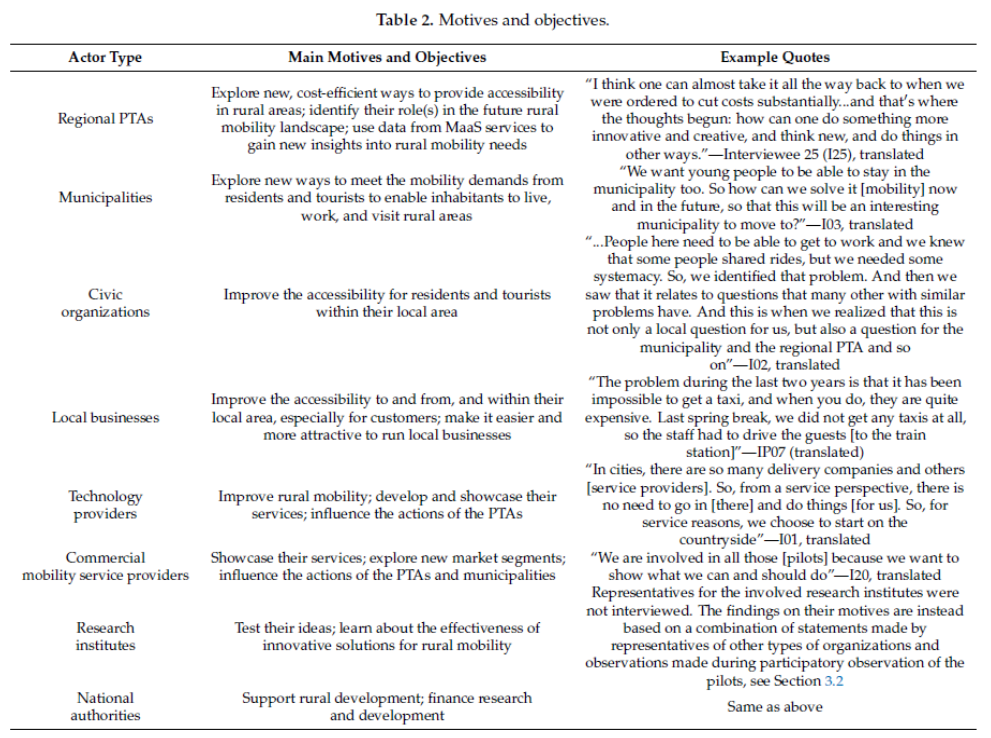

There were different opinions among the interviewees on how mobility services must develop to meet the needs of rural dwellers. Accordingly, their views diverged on what roles different actors should take in the future rural mobility landscape as well as on what actions needed to be taken to get to the envisioned state. The solutions to improve accessibility in rural areas, most frequently brought up by the interviewees, were to enhance the on-demand offering and to complement traditional public traffic with new types of mobility services. Still, some of the involved actors questioned whether one can expect a high service level in all types of areas.

The researcher stress that regardless of the PTAs’ role, there was a strong agreement among the interviewees that involvement of residents in the development and operation is key; an actionable and influential local civic organization was seen as a prerequisite for the adoption and diffusion of new types of mobility services, especially of those that require a certain level of penetration to function well, such as ridesharing.

Accordingly, the civic organizations saw themselves as the ambassadors of rural MaaS towards the residents as well as the actor that can make sure that the services meet the residents’ needs. Hence, it was argued that local civic organizations should be involved to a high degree already in the design phase.

Comparably, the commercial mobility service providers argued that they possess the most knowledge about mobility services, and therefore should be involved at an early stage as well. This would enable them to take part in the design of the service rather than only providing the requested services, which in turn would lead to better services, they argued. Several interviewees emphasized the important role of municipalities in rural MaaS.

Discussion

Both rural and urban MaaS are framed as solutions that aim to complement public transport and to reduce the perceived need of owning and using private cars. However, while this motive is grounded in problems such as road congestion, poor air quality, unhealthy travel choices, and greenhouse gas emissions when discussed for the urban context, the analyzed pilots were primarily motivated by the need to better provide access to rural dwellers, especially to people that either have limited or no access to private cars or people that want to reduce their private car dependency for other reasons. To put it simply, the interviewees’ focus was less on environmental sustainability and more on transport poverty.

In rural areas, the potential base of users is small, which makes services that require a critical mass to function well, such as ridesharing, vulnerable to external disturbances like changes in peoples’ everyday life, the interviewees argued.

This vulnerability was also, in some cases, linked to a high share of elderly residents who were less technology savvy. Other reasons for the limited activity in the pilots, proposed by the interviewees, included travel habits that are difficult to break, insufficient incentives to use the mobility services, limitations to the trialed systems and apps and therefore large entrance barriers for users, and uncertainty about roles and a lack of a culture of innovation within the involved organizations that led to low-value service offerings being trialed in the pilots. Hence, the actors involved in the studied pilots seem to have faced similar barriers as their urban counterparts.

Rural public transport has decreased in many places over the last decades due to a combination of factors including urbanization and austerity measures. Consequently, the levels of private car ownership, car traveling, and car dependency are typically higher in rural areas compared to the urban context. The article concludes that since car ownership and habitual car use are two of the greatest barriers to MaaS adoption, it follows that rural MaaS faces even greater challenges than urban MaaS.

Hence the authors understand that even though the analyzed pilots neither prove nor disprove the potential for rural MaaS, it can be assumed that the introduction of MaaS will not mitigate rural transport problems on its own. The study understands that to break car dependency and improve accessibility for non-car owners in rural areas, alterations that fundamentally change the context of rural traveling will be needed as well.

As argued within the literature on sustainability transitions, and recently exemplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, fundamental transformations of practices within socio-technical systems (such as personal transport) are more often than not caused by a combination of mutually reinforcing global events (such as the spread of the virus), change processes at system level (such as the travel restrictions and working from home policies that were mposed in the wake of the virus), and break-throughs of promising technology alternatives (such as telecommuting services).

Conclusions

The interviewees, more or less unanimously, stressed that rural MaaS must build on local needs and that local residents therefore should be involved in the design of the services. In particular, representatives of technology providers and local organizations emphasized a need for so-called place-based solutions, instead of one-size-fits-all solutions developed at a municipal, regional, or national level. All in all, anchoring with and involving locals seem to be essential components for rural MaaS developments no matter who the initiator is, in particular, to make sure that the services address real user needs and to put the services in position to attract sustained usage.

The researchers stress that rural dwellers are more willing than urbanites to actively participate in MaaS operations and to share private resources. Measures may need to be taken to ensure equal opportunities across rural communities when developing and disseminating rural MaaS. One of the conclusions of the article is that future research should, for example, explore how rural MaaS solutions can be co-created with residents in rural communities with less social capital.

The limited activity in the five analyzed pilots indicates that more research is needed into how one can motivate potential users to adopt and use rural MaaS solutions. The study underlines that future studies on rural MaaS users should, investigate who benefits from rural MaaS developments, and who does not. For instance, the reported analysis identified a risk that rural MaaS solutions might increase spatial injustice between rural communities. This risk should be further analyzed.

Additionally, the authors emphasize that future studies should investigate rural MaaS solutions’ potential to either alleviate or worsen transport injustice along other dimensions, such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, or ethnicity.