The previous articles in this series presented the main points that emerged from the seven working tables, organised by OCTO and The European House – Ambrosetti, and the supporting evidence.

This article presents an analysis of regulatory issues, which are considered a pivotal and enabling element for the success of any technological experimentation – in fact, even from the development activities of ongoing pilot projects with some City Administrations and other private actors, the need to understand how to manage the exchange of data between multiple stakeholders in the context of mobility (in the specific case of the experiments related to the implementation of some of the pilot projects identified by OCTO and The European House – Ambrosetti during 2021) has emerged.

In the ecosystem model for mobility embraced by OCTO and The European House – Ambrosetti, data and its exchange have to be seen as the enablers of innovative services for mobility aligned with OCTO’s Vision Zero (zero traffic, zero accidents and zero pollution). As already mentioned, in the course of the 2022 activities, the topic of data exchange proved to be central both in the working tables and in the realisation activities of the pilot projects.

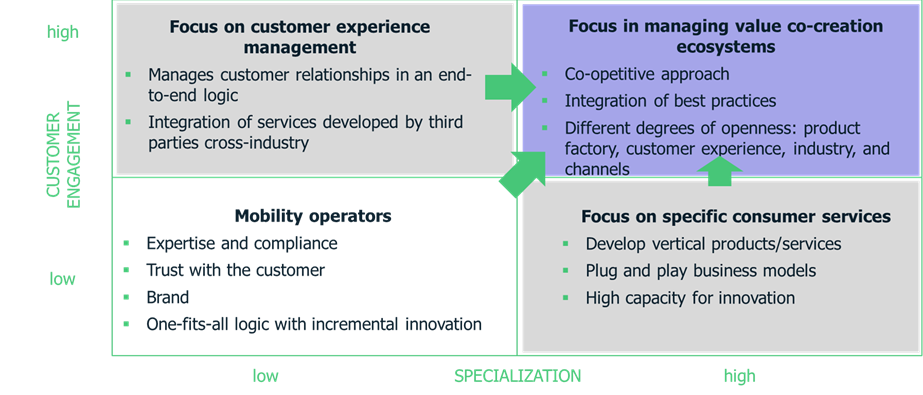

Already in 2021, data collection and exchange had been identified as central elements for the development of the “Italian way to connected mobility”. In the vision of OCTO and The European House – Ambrosetti, the possibility of exchanging information between different sources and subjects allows the entry of new specialised players capable of effectively and efficiently developing new verticals and service areas or new customer experience models.

Figure 1 The vision of OCTO and The European House – Ambrosetti: focus on managing value ecosystems

The concepts of data sharing and ecosystem models are fundamental to introducing the normative topic addressed in this article. Data sharing is indeed an enabling element in three key areas of mobility:

- Connected infrastructures – data are key to building smart contexts in which infrastructure, vehicles and road users are able to talk to each other;

- New mobility models – e.g. Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), data enable the definition of new competitive spaces and are an enabling factor for efficient mobility services, built around the MaaS paradigm;

- Innovative mobility services – within the already mentioned contexts, connected infrastructures and MaaS models, it is possible to idealise the co-participation of different actors in the co-creation of new service offers, made possible through the exchange and processing of data.

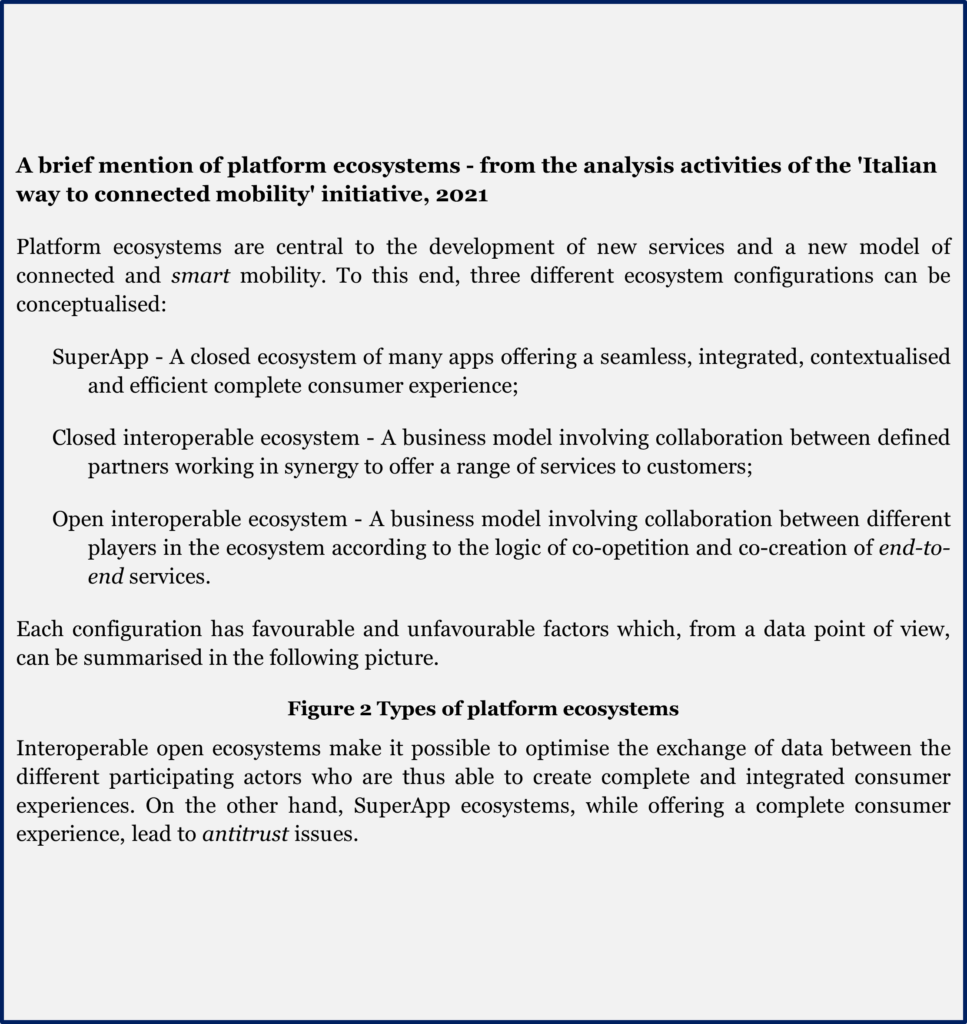

In this sense, the pilot projects of OCTO and The European House – Ambrosetti envisage the combination of the areas described above to create a new ecosystem of connected and smart mobility. In order to identify the development opportunities for the “Italian Way to Connected Mobility” and define the areas to be focused on, the analyses were focused on the in-depth study of three normative fields:

- Personal data management – regulated, at European level, by the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), which regulates the management of personal data and its exchange;

- Management of data exchanged on digital platforms – managed from 5 July 2022 by the Digital Packages Act, consisting of the Digital Service Act and the Digital Market Act and aimed at regulating the exchange and use of data within digital platform ecosystems;

- Finally, user trust-building – regulated by the Data Governance Act, which came into force in June 2022 and aims to regulate certain opportunities for data exchange (e.g. Open Data collected by public administrations) and to promote the creation of Data Spaces at European level in strategic areas, including mobility.

Figure 3 The three regulatory frameworks analysed in this article

Within a connected and smart mobility ecosystem – made up of interconnected infrastructures, MaaS services and services developed by different types of actors – different types of data are generated and exchanged, from data on the movements of various means of transport to location data, from aggregated data of mobility service users to data generated by city infrastructures.

As is well known, the GDPR regulates all data that are considered ‘personal’, i.e. data that are directly referable to a specific person.

In this sense, with respect to data collected and managed within a connected ecosystem, it is very important to go and define the applicability of the GDPR regulations on a case-by-case basis. This process is fundamental and encouraged by the European legislation that promotes the collection and use of personal data whenever there is a “legitimate interest” or “public interest” – these cases are in addition to explicit consent (considered by the literature as a possible limiting factor to the full application of the GDPR in contexts of exchange of large amounts of data, so-called Big Data), the presence of a contract, legal obligation and vital interest.

European legislation defines certain use cases in which an actor – public or private – is entitled to collect and use personal data, including:

- Creating statistics to promote better management and future development of the urban environment;

- Define city-level policies based on objective and collected data with respect to the specific context;

- Monitor the status and operation of a fleet of vehicles in order to implement fleet optimisation programmes.

For the purposes of developing the Italian way to connected mobility, the issue of personal data management and exchange certainly needs attention. In particular, considering that many of the pilot projects of OCTO and The European House – Ambrosetti envisage the involvement of City Administrations, it is key to consider the above-mentioned case studies and to investigate, with respect to individual use cases, the applicability or non-applicability of the GDPR regulations.

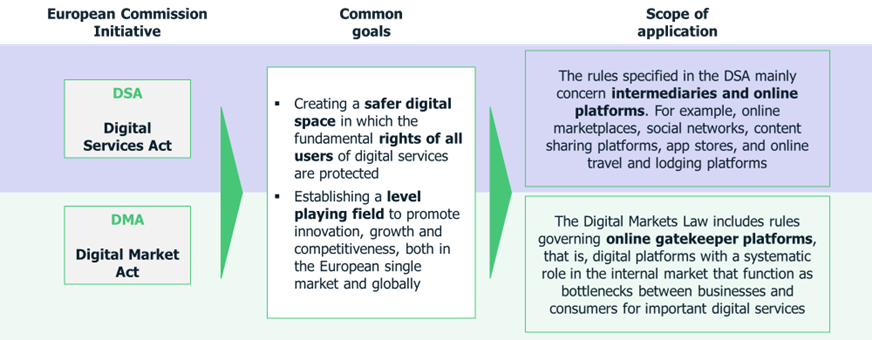

Secondly, for the purposes of creating a digital platform ecosystem, it is important to analyse the regulations contained within the Digital Packages Act, i.e. the body of legislation, adopted by the European Commission on 5 July 2022, which aims to promote greater security for users with respect to the use and management of their data.

The Digital Packages Act consists of the Digital Service Act, aimed at regulating digital intermediaries and platforms, and the Digital Market Act, aimed at regulating the scope of action of platforms that aggregate data collected from users in the first instance.

Figure 4 Key elements of the Digital Service Act (DSA) and the Digital Market Act (DMA)

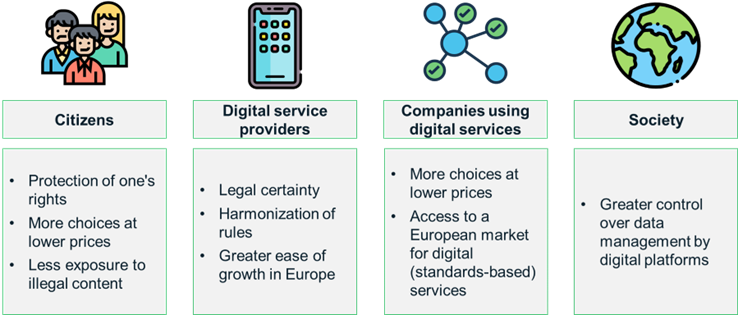

In the vision of the European Commission, the Digital Service Act is meant to protect the data of users of digital services, to improve the management and increase the accountability of digital platforms, and to promote new innovation processes – based on greater certainty of data collection and exchange. The full achievement of these objectives will foster the creation of a number of benefits for market stakeholders, as depicted in the image below.

Figure 5 The main benefits enabled by the Digital Service Act as seen by the European Commission

The Digital Market Act is always aimed at regulating digital platforms, but in this case it directly involves the actors defined as ‘gatekeepers’, i.e. those platforms that collect data from users and feed them into digital ecosystems of data exchange. Specifically, the main benefits of the Digital Market Act are:

- create a fairer environment for companies that depend on gatekeepers to offer their services;

- eliminate unfair terms and conditions that limit the development of innovators and technology start-ups that exploit the data collected by gatekeeper platforms;

- offer consumers more choice in services and the possibility of switching providers to have direct access to fairer services and prices.

In order to realise these benefits, the European Commission has defined the activities that will have to be allowed by gatekeeper platforms. In particular, these platforms will have to enable interoperability between their own services and those developed by third parties, allow users to access their own data collected on the platform, and allow companies operating on the platform to carry out promotional activities aimed at signing contracts outside the gatekeeper platform.

Finally, the last piece of legislation to consider in the development of a digital ecosystem for connected and smart mobility relates to the very recent Data Governance Act, which came into force on 23 June 2022 and will be applicable from September 2023.

The Data Governance Act is an instrument considered by the European Commission to be a ‘key pillar‘ to concretise the European Data Strategy. In particular, the Data Governance Act intends to foster data portability and promote greater interoperability between data generated by different sources. To this end, this act supports the creation and development of a common Data Space at the European level that will be realised thanks to the co-participation and collaboration between public and private actors and will collect data on certain areas considered strategic, including mobility.

In the development of this data exchange and collection system, the European automotive industry points out the need to develop the system in line with the principle of technology neutrality. This indication is intended to avoid a predefined set of technologies for data collection and sharing at European level, effectively excluding the maturation of innovative technological tools. The new technologies will have to be developed following the operating standards of the Data Spaces, but leaving it up to the individual market players to innovate modalities, sources and systems of data collection and transmission.

The regulatory frameworks discussed in this article are the key elements to be considered in the development of a new connected and smart mobility ecosystem. In the next article in this series, some central aspects of regulation applied to the specific context of mobility will be explored, in particular the aspects of Connected Infrastructure (C-ITS), Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) and Connected and Automated Driving (CAD).

Author:

The European House – Ambrosetti