Researchers Yeon Baik, Russell Hensley, Patrick Hertzke and Stefan Knupfer from McKinsey, published an article on McKinsey Center for Future Mobility in September 2021, named: “Why the automotive future is electric”. The article provides an a-up to date review on this issue. Here are some of the key issues.

The future looks bright for electric-vehicle (EV) growth. Consumers are more willing than ever to consider buying EVs, and sales are rising fast. Most major markets have consistently registered 50 to 60 percent growth in recent years, albeit from small bases. More new models from a growing cadre of automotive OEMs make finding a suitable EV easier: in 2018 alone OEMs launched about 100 new models and sold two million units in total globally. Likewise, performance improvements continue with respect to range, performance, and reliability. Regulations in major car markets—namely China, the European Union, and the United States—compel OEMs to produce more EVs and encourage consumers to buy them.

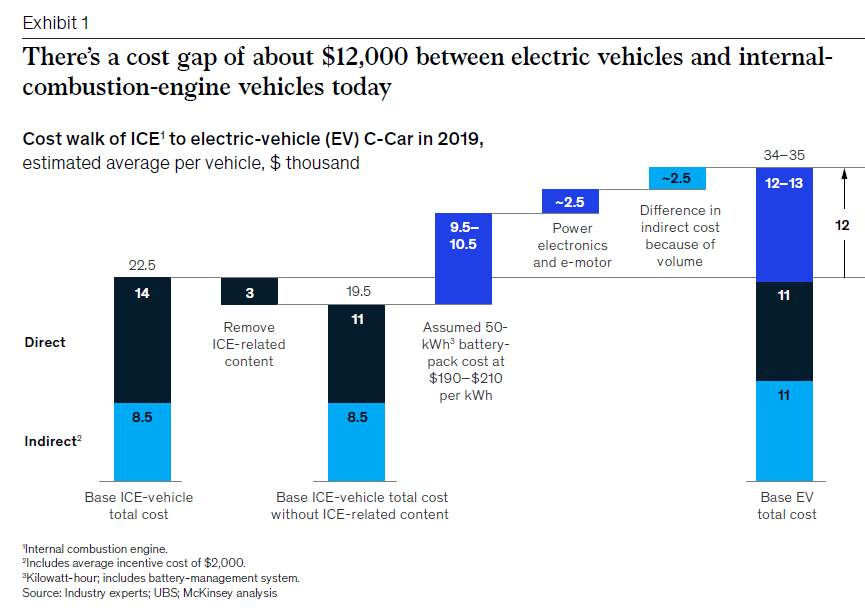

However, the study points out that there is a problem: today, most OEMs do not make a profit from the sale of EVs. In fact, these vehicles often cost $12,000 more to produce than comparable vehicles powered by internal combustion engines (ICEs) in the small- to midsize car segment and the small-utility-vehicle segment. What is more, carmakers often struggle to recoup those costs through pricing alone. The result: apart from a few premium models, OEMs stand to lose money on almost every EV sold, which is clearly unsustainable.

Many carmakers appear to be resigned to this fate, at least for now. Battery costs represent the largest single factor in this price differential. As industry battery prices decline, perhaps five to seven years from now, the economics of EVs should shift from red to green. The authors stress that their analyses show that better options exist, even today, to accelerate the industry toward profitability from both product and business model perspectives.

Accelerating toward profitability

Optimize electric-vehicle designs for the market

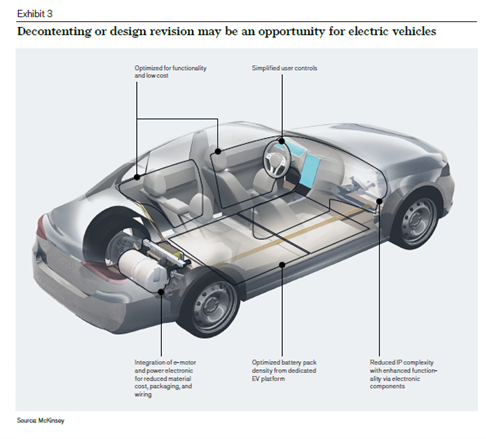

The researchers believe that OEMs can reduce their EV costs by $5,700 to $7,100 by pursuing strategic decontenting paired with a dedicated EV platform. This could be accomplished by leveraging new freedom in design unlocked by using electric rather that ICE subsystems and applying leading strategies in low-cost ICE design and from cutting-edge EV-focused OEMs. OEMs that choose to make a BEV or PHEV from a modified ICE platform to limit capital investment will often have to sacrifice higher material costs driven by the “overdesigned” platform and face challenges in battery packaging, not only in the same capacity (sacrificing range), but also in a less cost-efficient manner, potentially making them less exciting to consumers.

Design simplifications and

value-neutral decontenting

OEMs can take lessons from leading e-vehicle concepts, for which our proprietary teardown study revealed that cockpit, electronics, and body simplifications netted up to $600 in reduced costs, without removing core feature content tied to value generation for the OEM.1 Eliminating extra displays, buttons, switches, wiring, modules, and additional structural components, as well as reducing the overall design complexity, drove major savings. The study stress that their experts also noted that OEMs can only capture all of these material cost savings when using a dedicated EV platform that enables better packaging of interior cabin space, power electronics, motors, and battery packs.

Optimizing for urban mobility

For many customer segments, today’s EVs offer either too little driving range, such as smaller EVs with ranges of fewer than 100 miles, or too much, such as luxury EVs with ranges of approximately 300 miles, when compared to actual driving patterns. The average vehicle miles traveled (VMT) for an urban population is around 20 miles per day in the United States, and it increases to around 30 miles per day when accounting for demographic groups that drive more.2 Assuming today’s battery efficiency in kilowatt-hours (kWh) per mile, a potential sweet spot for urban customers is approximately 25 kWh of energy. However, if we take into account that the consumer preference to use the same vehicle for suburban and occasional rural travel, the optimal battery capacity increases to approximately 40 kWh, equating to~250 kilometers, or about 160 miles, based on average VMT in rural areas. A reduction in battery capacity to 40 kWh, from 50 kWh, would save $1,900 to $2,100 today, while the range would still enable most consumers, especially those in urban environments, to complete trips without any sacrifice to their daily routines.

Final assembly optimization

The investigation also highlights that a purpose-built EV platform is simpler to assemble and could deliver up to $600 in savings per vehicle in lower fixed-cost allocation. Those savings come from having fewer components to assemble in an optimized EV platform and requiring less capital in EV-only plants versus complex plants that combine ICE-vehicle and EV lines.

Partnership during the transition

During the next five to seven years, as the industry transitions toward electrification but struggles with profitability, automakers should more strongly consider partnering and collaborating ºwith competitors. At a time when OEMs face the possibility of retooling numerous models and platforms for electrification, collaborating with other OEMs can reduce the fixed-cost burden of R&D, tooling, and plants. Benefits will be especially high if OEMs can share EV platforms and plants, which can still enable multiple model variants. These alliances will also be most beneficial when they enable higher-volume procurement of the same battery cells and power electronics to take advantage of scale that is otherwise elusive when going it alone. In fact, some automakers have already announced a range of different global partnerships focused on reducing the cost of designing and producing EVs.According to the study, the impact of two OEMs co developing a dedicated EV platform, which could lead to two to three times the volume spread across a similar fixed-cost base—would reduce costs by $1,500 to $2,000 per vehicle.

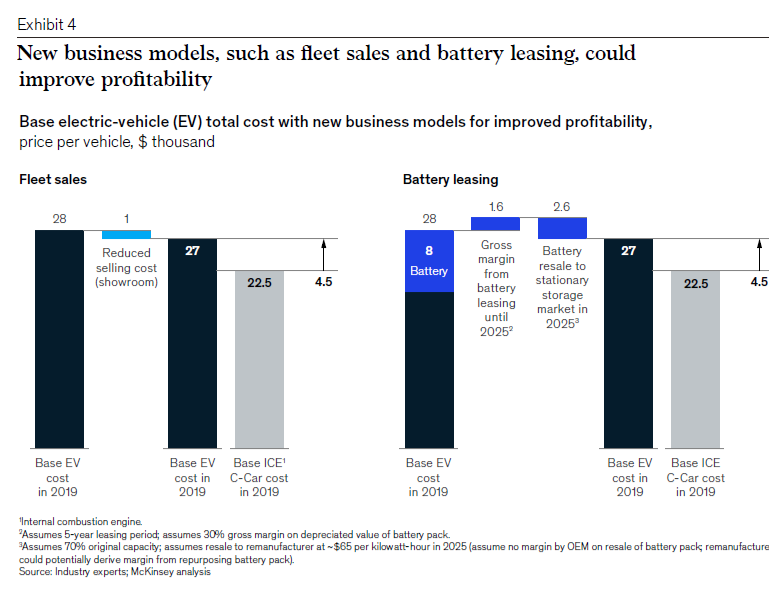

Exploring new business models

Automakers that take a bolder approach to closing the profitability gap can also experiment with a range of new business models for niche segments. Example ideas include targeted direct sales to fleets and battery leasing.

Economically, it makes sense to target fleet customers with EV models, given that these fleets typically fall into a high-mileage category in which the total cost of ownership (TCO) of EVs is beneficial—and they prioritize TCO higher than other buying factors. Direct selling to these customers can reduce selling costs by about $1,000 per vehicle by circumventing showroom costs. Given the positive business case for fleet customers and their more predictable and simple charging logistics, these customer segments are early use cases for high EV take rates.

OEMs could offer to lease batteries separately from the vehicle and resell older batteries to the stationary storage market for secondary use. Battery leasing has a potential to attract consumers who shy away from purchasing an EV due to uncertainty in performance and degrading capacity of batteries today. OEMs operating a successful battery-leasing program could add more than $1,000 in revenue per vehicle during the assumed lease term of five years. A customer would be paying a monthly fee to lease the battery, with an assumption of added margin on the depreciated value of the battery pack.3 This could be an increasingly viable profit-generating idea, but we still assume that this will only appeal to a minority of customers today. The research highlights the example of Renault ZOE: it offers battery-leasing options to customers on its 41-kilowatt-hour battery-pack model, starting at £59 per month for 4,500 annual mileage up to £110 per month for unlimited mileage.

Conclusion

While not as profitable as ICE vehicles today, the study concludes that EVs have the potential to reach cost parity with and become equally—or even more—profitable as ICE vehicles by around 2025. McKinsey and other industry experts have conducted detailed studies on the potential cost trajectory for EVs, including battery-cost and efficiency improvements, power-electronics scale economies, and indirect cost reduction based on increased volume production. The authors believe these can unlock $5,100 to $5,700 in cost reductions per vehicle. Based on these analyses, an OEM could expect to break even in cost with EVs compared to ICE vehicles, and thus even achieve a profit margin of 2 to 3 percent per vehicle, in 2025. This scenario holds true in the absence of any premiums in pricing paid by consumers or any subsidies provided by governments. Application of the newer business models described above are also excluded here.

The key debates are thus:

— applying more ambitious cost-reduction approaches to EVs, including design

simplification, value-neutral decontenting, and aggressive purchasing strategies

— evaluating new potential partnerships with competitors to share R&D, tooling, and production costs for new EV platforms

— considering more creative use of alternative EV-specific business models that can boost margins

The researchers conclude that consumers, city dynamics, regulators, and competitors will increase pressure on most OEMs to switch more quickly from ICE vehicles to EVs, often with little consideration of EV economics.