Researchers Donald A. Chapman, Johan Eyckmansand Karel Van Acker published an article in MPDI in October 2020 named “Does Car-Sharing Reduce Car-Use? An Impact Evaluation of Car-Sharing in Flanders, Belgium”. The article provides an a-up to date review on this issue. Here are some of the key issues.

Private car-use is a major contributor of greenhouse gases. Car-sharing is often hypothesized as a potential solution to reduce car-ownership, which can lead to car-sharing users reducing their car-use. However, there is a risk that car-sharing may also increase car-use amongst some users. Existing studies on the impacts of car-sharing on car-use are often based on estimates of the users’ own judgement of the effects; few studies make use of quasi-experimental methods. In their paper, the impact of car-sharing on car-ownership and car-use in Flanders, Belgium is estimated using survey data from both sharers and non-sharers.

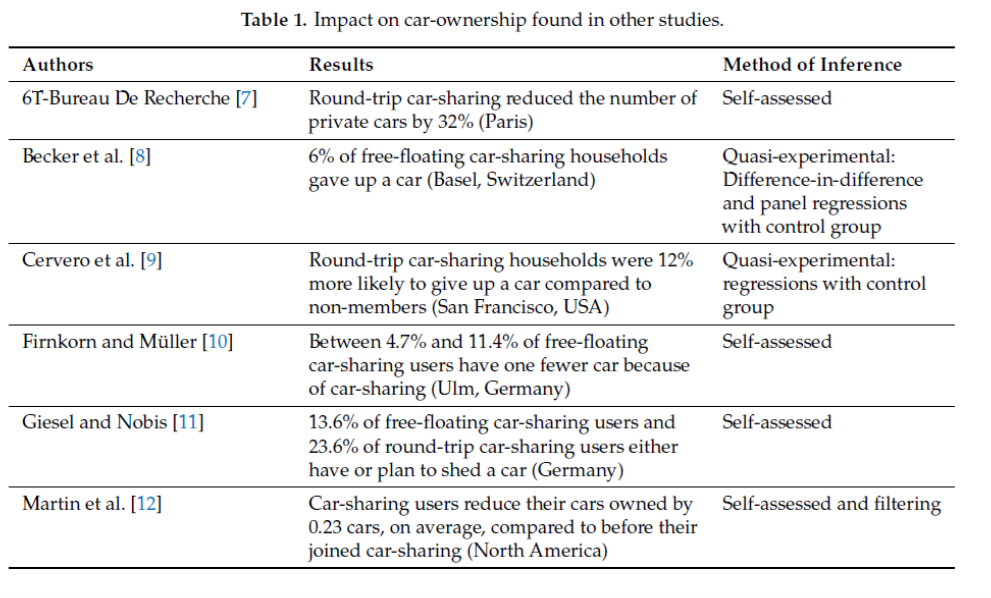

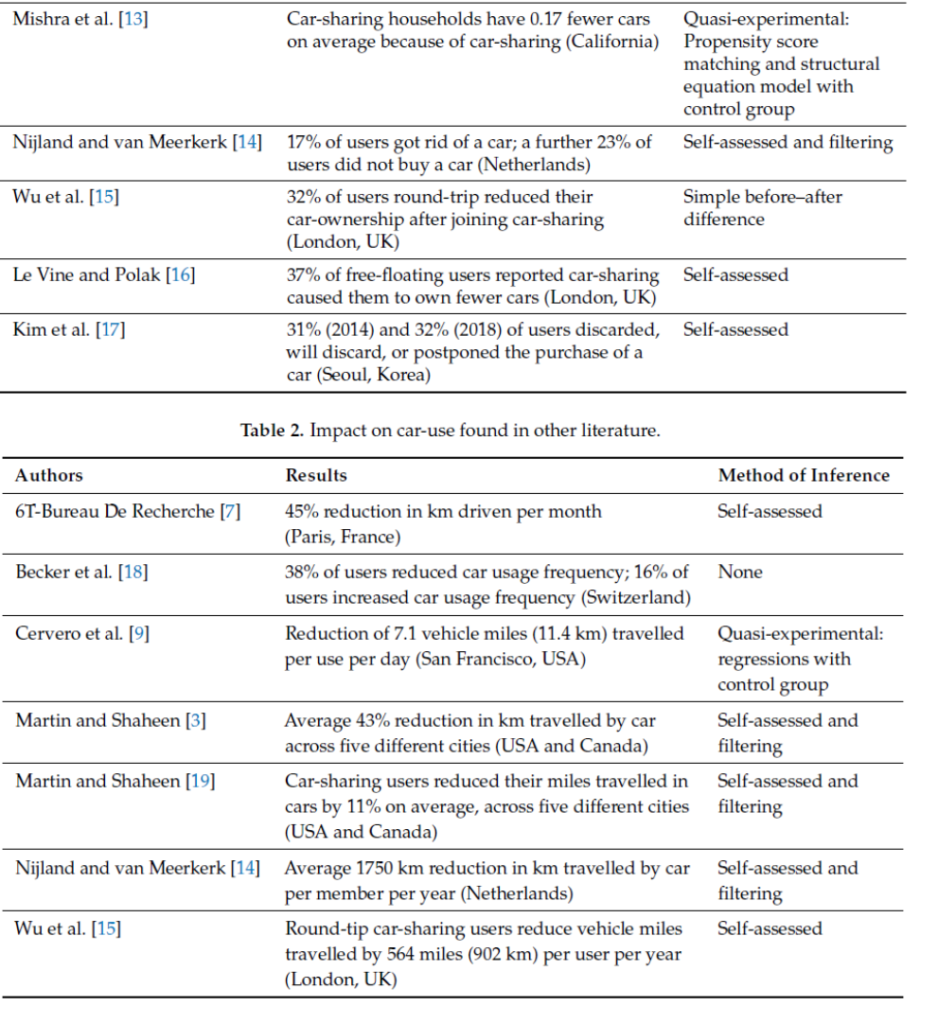

The results show that the car-sharing may reduce car-use, but only if a significant number of users reduce their car-ownership. Policy intervention may therefore be required to ensure car-sharing leads to a reduction in car-use by, for example, discouraging car-ownership. There have been a number of studies that investigate the impacts of car-sharing on car-ownership and car-use, as summarized in the following tables.

Car-sharing is believed to be a potential solution that could induce behavioral changes through a reduction in car-ownership and of car-use. A consistent finding among investigations in this field is that a significant number of car-sharing users reduce the number of cars they own, either because they sell or scrap a car, or because they do not purchase a car they otherwise would have bought. In contrast, a prospective study of potential car-sharing members in Korea found that car-sharing may lead to an increase in GHG emissions due to an increase in car-use amongst some users.

Other investigations find that car-sharing users reduce their car-use, on average; some studies explain this by observing that car-sharers who have fewer cars because of car-sharing reduce their car-use, while those whose car-ownership is not affected increase their car-use. The impact among the former group is normally larger than the latter group; in other words, users who have fewer cars reduce their car-use by more than the users whose car-ownership is not affected by their car-use.

The importance of changes to car-ownership and car-use, then, are central to the realization of environmental benefits. Over or underestimating the impact of car-sharing on car-ownership can lead to an over/underestimate of the impact on car-use.

The researchers highlight that to ignore it introduces a risk of bias: if all users without a car are assumed to have gotten rid of a car because of car-sharing, then the impact of car-sharing on car-ownership would be overestimated, thus also affecting the estimated impact on car-use.

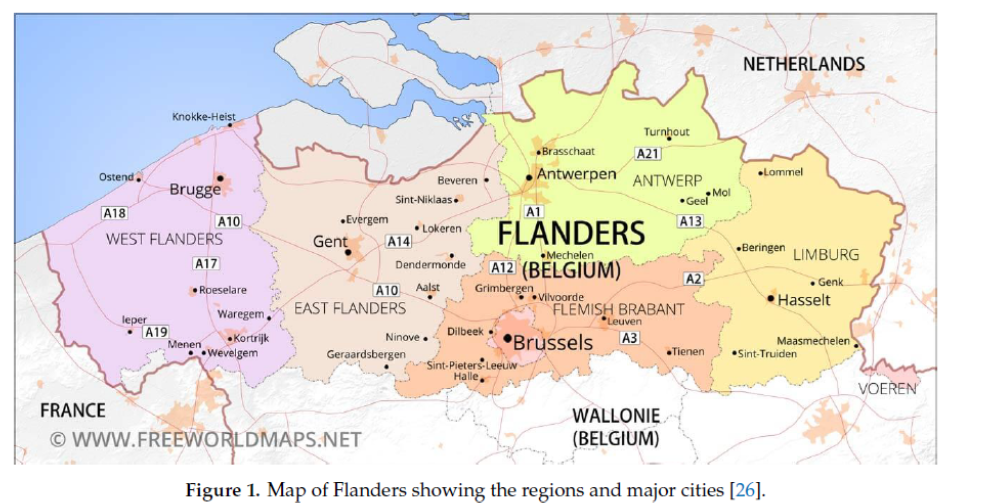

A case study

Flanders is the Dutch speaking region in Belgium with a total population of 6.6 million and a population density of 487 inhabitants per km2. A report from 2019 found that there are approximately 75,000 car-sharing users in Flanders. The percentage of car-sharing users in Flanders is approximately 1.1%

The goal of this study is to estimate the impact of car-sharing on car-use. This estimation is, however, complicated by the relationship between the impact of car-sharing on car-ownership since the number of cars a person owns affects how much he/she will use a car. For example, the introduction of car-sharing to one’s neighborhood may cause an inhabitant to join car-sharing and to sell his/her car (or one of the cars in the household), reducing the user’s access to private cars. This change in access (from having one private car fewer but having access to car-sharing) is likely to reduce how much he/she drives. In contrast, an inhabitant who does not have a car (and had no plans to buy one, thus his/her car-ownership is unaffected by the introduction of car-sharing) will increase his/her access to cars by joining car-sharing, which can lead to an increase in car-use.

By manipulating the incentives offered, car-ownership may be reduced at the expense of a more multi-modal lifestyle that includes occasional car-use through car-sharing, explain the study. For example, in-kind incentives such as public transport passes, bike sharing memberships or car-sharing memberships may lead to residents choosing to forgo the replacement of their cars. However, making car-sharing cheaper may result in substitution effects that reduce public transport use instead of car-use.

These policies involve different levels of government (federal, regional and city/municipal) and different actors (car-sharing firms, company car fleet operators, businesses, employees, consumers) that make a coordinated policy mix a complex multi-level governance problem, especially in Belgium.

The authors point out that Low emission zones (LEZs) present an opportunity for city governments to affect car-ownership. LEZs have been introduced in many Flemish cities aimed at reducing air pollution caused by particulates; to ease the transition, residents are offered incentives to scrap cars that no longer meet LEZ requirements. By manipulating the incentives offered, car-ownership may be reduced at the expense of a more multi-modal lifestyle that includes occasional car-use through car-sharing. For example, in-kind incentives such as public transport passes, bike sharing memberships or car-sharing memberships may lead to residents choosing to forgo the replacement of their cars. Cash incentives, however, risk residents offsetting the cost of a new car purchase instead.

Conclusions

Car-sharing may be a promising system that can deliver a reduction in car-use, and consequently help to lower GHG emissions, air pollution, and traffic congestion. Existing studies have tended to show that car-sharing does lead to lower car-use; however there have been very few studies making use of quasi-experimental methods, and instead most impact studies rely exclusively on users’ own assessment of their change in behavior.

The results show that the key driver in car-sharing being able to reduce car-use is its effect on car-ownership: users who reduce car-ownership will reduce their car-use (LAUs), while those for whom car-sharing has no effect on car-ownership will increase their car-use (HAUs). According to the results of this study, only by assuming that car-sharing has a large effect on car-ownership will car-sharing lead to a statistically significant reduction in car-use.

This suggests that policy intervention may be required to ensure the full environmental benefits of car-sharing are realized. Policies should focus on encouraging car-sharing at the expense of car-ownership, for example, by increasing the tax burden associated with car-ownership, or by reducing the convenience of car-ownership through stricter parking regulations. However, policies that make car-sharing more attractive (e.g., through tax breaks or preferential parking/traffic policies) risk attracting HAUs as much as LAUs, and consequently risk stimulating more car-use. Such policies should therefore be subject to rigorous ex-ante and ex-post evaluations to ensure reductions in car-use actually occur.

This study stress that further research is also needed to better understand why some users see car-sharing as a replacement for car-ownership. This could help policymakers better understand how to specifically target such users.

The estimated impact of car-sharing on car-use and the sensitivity of this to car-ownership effects highlighted in this study show the need for more robust, quasi-experimental research into the impacts of car-sharing on both car-ownership and car-use. Future studies could build on this research by using either longitudinal data or an instrumental variable approach that would allow both of these impacts to be estimated without the need for self-assessment. However, collection of this data remains a challenge, especially while car-sharing is a niche activity.