The future of the car is also depending on chips production. Europe, lagging behind in manufacturing, is accelerating pace due to funding and legislation.

European chips, the Breton plan arrived on February 8, 2022. Long-term investments of approximately 50 billion euros should revitalize a troubled sector from an industrial standpoint and make Europe self-sufficient to face future challenges from vehicles (electric and otherwise) to artificial intelligence. A similar plan has been proposed in the States, raising a number of observations (at this link, those from Forbes).

In Europe, the chip issue went under the public opinion scrutiny when it was paired to the car crisis. Moving on from this starting point, let’s try to have a closer look at the scenario we are facing.

How many chips do you need in a car?

An older Ford Focus typically uses around 300 chips, while today an ICE uses around 1,000 chips. An EV is equipped approximately with 3,000 chips, while a Tesla has 3,500 chips or more on board.

Cars are equipped with small chips

Chips being used in cars are mostly small, low-tech, and very low-cost. Even computers, smartphones and other digital devices use chips, but in these cases one or more of those chips contain billions of transistors and imply a more complex technology and a much richer economy. The huge number of chips used in cars generates a small fraction of the turnover of chip manufacturers, and the profit margin is even smaller. To cut a long story short, this is not the first choice.

Let alone the number and size of the chips, there is no denying that overall vehicles production was drastically reduced in 2021. Generally, the reasons are to be found, first in the recession due to the pandemic and, second, in the shortage of chips. In 2021, major Western endothermic car makers produced less than 1 million cars each However, it is not certain that if they had produced them, they would have sold them: car usage patterns are changing. Eastern manufacturers were less affected, also due to their proximity to China, the main chip maker country. Tesla, who is not Chinese, did not suffer to much because of a more elastic approach that allows, with little effort, to use chips from various manufacturers. This elasticity, despite what the industry 4.0 is boasting, does not belong to other Europeans or Americans manufacturers.

Europe must return to manufacturing chips

Reading Breton’s project, it seems that with 50 billion in several years, Europe will become competitive in the microelectronics sector. In similar period of time, the PNRR would allocate approximately 200 billion to Italy alone.

Let’s be clear: Europe is totally out of the game when it comes to chip manufacture and the chips we are talking about today may not necessarily be strategic in 2030.

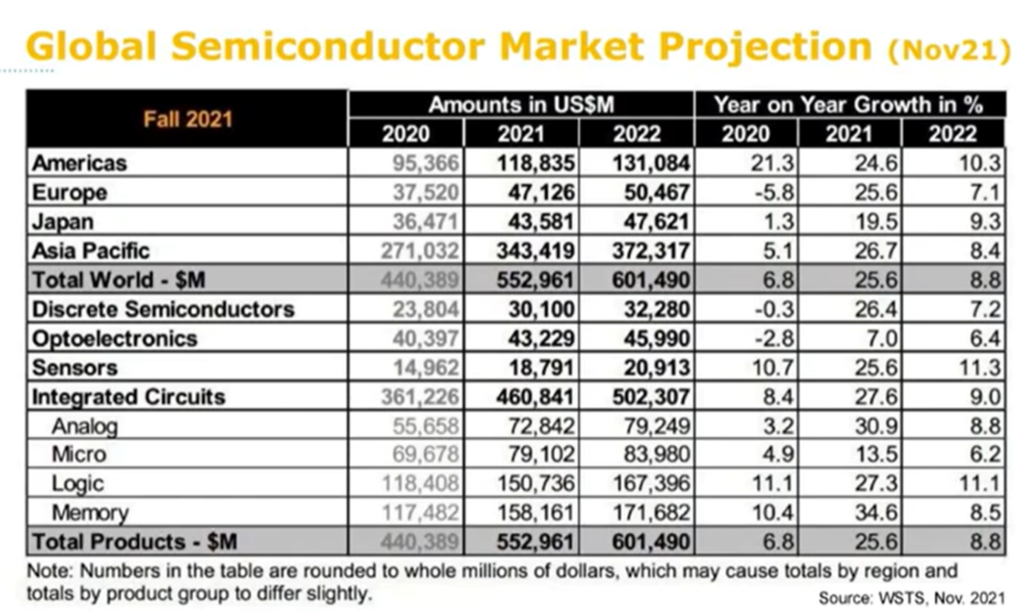

According to Wsts.org, World Semiconductor Trade Statistics, numbers for Europe in 2022 are far from encouraging (edit as of Feb 14th, 2022).

Europe in general, and Italy in particular, is arrogant, self-referential, and completely unable to set up an industrial policy. You can see it in the electric vehicles industry, in the smiles caused by the talks about the hydrogen supply chain, by the oblivion affecting the issue of chips manufacturing.

The arrogance is in keep considering Europe the cradle of civilization and research, even when it comes to chips. This has not been true for a while now. The mistake made with chips at the time was made again with the cloud and is being replicated indefinitely, even with artificial intelligence (not to mention space – despite the very interesting contract for with Thales Alenia -, and quantum computing).

Thierry Breton’s action # 1: investments

What is Europe is doing is introducing a pompous Semiconductor Act, an investment plan that might bring chips production back to the Old Continent.

Appropriate plants – the silicon foundries, but there are also other types of plants -, require spending figures in the order of 10 billion euros for the start-up phase only, and additional very high figures for maintaining production. They theoretically go to full capacity in about 5 years, but in some cases, they can be up and running in 3 years. It is no longer possible to build them exclusively on private capital; on the contrary now the system is based almost exclusively on public money. This is easier in China and Taiwan, less so in Europe and the US. This is way Europe is trying to change at least a few things.

Europe estimates its local production between 5 and 10% of the world total. The investment plan would allow this percentage to move up to 20% of production within 2030.

The European plan foresees investments of 40/50 billion euros. The plan’s directives should be five:

1. push on research, development and innovation;

2. primacy in design and manufacturing;

3. new rules on state aid, to counter less “liberal” views of the economy;

4. new tools to operate on the supply chain also in a preventive way;

5. Wider opening to SMEs and, we suppose, start-ups.

Intel invests in Europe

Having probably understood this is the right time, Intel unveiled an 80 billion euro plan in new investments. After some not really positive years, the historic company that invented the commercial microprocessor (thanks to the Italian Federico Faggin) and the x86 architecture that changed the world, is back to great shape also thanks to the choices of the new CEO, Pat Gelsinger, who has spent a lifetime in the company.

There should be two (if not more) new factories in Europe. Despite the usually disappointing hopes from Italy, the good factory should be located in Germany. Italy might get the packaging plant, which is to say arrange packaging (low value activity) starting from components made elsewhere (high value activity). It should be noted that semiconductor manufacturing requires an enormous amount of clean water, an essential assessment in terms of environmental sustainability goals. Packaging does not pose such problem.

Thierry Breton’s action # 2: protectionism

In addition to research, eastern countries also have the financial leverage to impoverish Europe. Despite the free model, the first idea that came to mind was to block acquisitions to run for cover. Therefore, several less liberal and more protectionist operations are already underway. For example, there is an attempt to stop the acquisition of the British based Arm (owned by the international group Softbank) by the US Nvidia: both the US FTC and the EU have appealed, and the British agency CMA has also taken a stand. (Update: on February 7th, the stop to the acquisition was announced: ARM will go to market with the new CEO, Haas).

Similarly, the German government held back the acquisition of Siltronic by the Taiwanese of Globalwafer.

Will it be enough?

Difficult to say: the doubts of timeliness are added to the risk of feasibility. The European chips ecosystem is less jagged than the batteries ecosystem, with less actions and fewer disappointments. It is true that over time the EU has sought also industrial cohesion beyond nationalisms, but it is also true that we are not yet sufficiently cohesive.

Besides, events in Ukraine could concur in slowing down global chip production. Any sanctions against Russia could block the export of neon, one of the noble gases used in the production stages; according to Reuters, 90% of the neon used in US factories comes from Ukraine. This is why the news that the Korean company Posco has been able to produce neon it is of global relevance. Another key element, palladium, is mined in Russia and it has so far been exported all over the world.