Evaluation of Effects of Car Sharing in Amsterdam

Researchers Ana María Arbeláez Vélez and Andrius Plepys from the International Institute Industrial Environmental Economics, Lund University Sweden, published an article in “Sustainability” regarding car sharing as a strategy to address emissions. The article provides an up- to-date review on this issue. Here are some of the key issues.

The transport sector is a significant contributor to climate change, due to its large emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG). In 2017, the sector generated 1.1 Gt of CO2-eq, corresponding to about 25% of the total emissions in the EU. Seventy-two percent of emissions came from road transport, of which 44% was from passenger cars, 19% from heavy goods vehicles and buses, and 9% from light commercial vehicles. This sector is also responsible for other negative effects, such as air pollution, noise, and traffic congestion. Increasing urbanization, affluence, and car ownership are exacerbating these effects.

The modalities of shared mobility are often seen as promising options for sustainable transport. Examples include bike, car, or ridesharing. Shared mobility gives access to a vehicle or space in a vehicle for a short period of time (hours or days). The user of the vehicle pays a fee for the time or distance traveled, meaning they are not burdened with the costs of ownership.

Car sharing or business-to-consumer (B2C) car-sharing is when several people have access to the same vehicle; these vehicles are owned by companies that rent per hour or per day. In the case of personal vehicle sharing or peer-to-peer (P2P) car-sharing, private individuals rent their vehicles to others and receive financial compensation in return. The transaction and matchmaking take place via an IT platform. Ridesharing refers to individuals sharing the same vehicle to travel because it is convenient due to their departure time and destination. These vehicles might be privately owned. On-demand ride service is a similar service to taxis, where the driver owns the vehicle and picks up individuals, offering a flexible door-to-door service. Bike-sharing is when several people have access to the same bike, and e-scooter sharing is offered through a similar service to bike-sharing

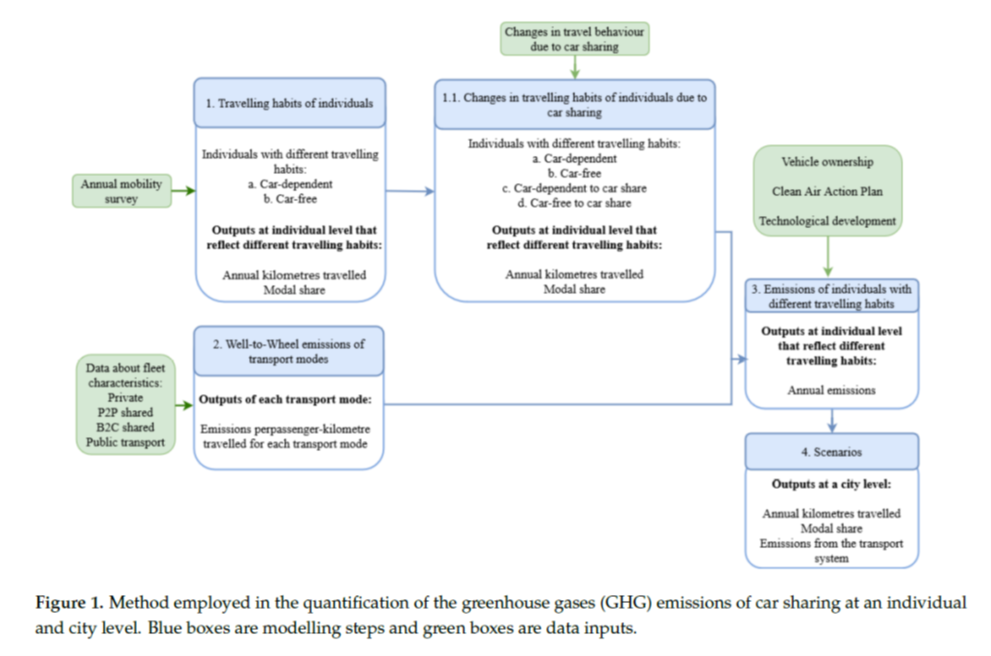

Car sharing usually induces changes in individuals’ car ownership, total travel distances, and mobility modes. These changes may imply a reduction in GHG. Available studies measure the effects of shared mobility at an individual or organizational level, but they fail to provide a city-wide perspective. The study concluded that there is a need for sustainability assessments that capture the effects of shared mobility on the urban transport system, to enable the development and implementation of effective transport policies.

The researchers highlight that the objective of this study, which is based in Amsterdam, was to assess potential changes in GHG emissions at an individual and city level, by considering changes in the travel habits of individuals who engage in car sharing.

Effects of Car Sharing on Emissions at Individual Level

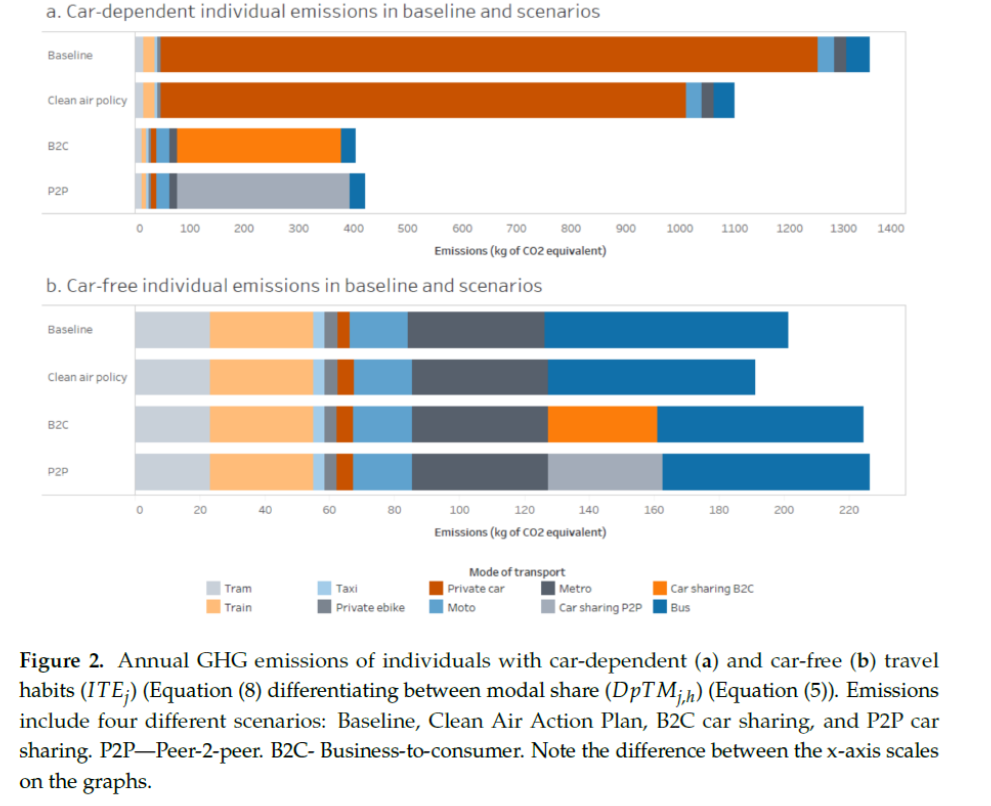

Once individuals engage with car sharing, they tend to adjust their travel habits. People might reduce their annual distance traveled by car, replacing journeys with more emission-efficient transport modes and thereby reducing total emissions. Nonetheless, the authors stress that findings from their research indicate different consequences in transport emissions when individuals engage in car sharing. Individuals shifting from car-dependent to car-sharing travel habits reduce their emissions, while those shifting from car-free to car-sharing increase them. Emissions savings from people who migrate from car-dependent to car-sharing appear to be significant—a reduction of about 68% of the WTW, which can be attributed to disposing of owned vehicles and consequently a modal shift.

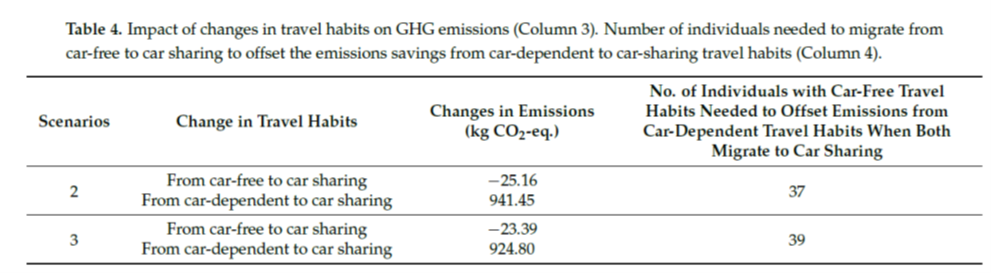

The savings in emissions from individuals who migrate from car-dependent to car-sharing are clearly higher than the increase in emissions from individuals who migrate from car´free to car-sharing travel habits.

Effects of P2P and B2C Car-Sharing Fleets on Emissions

According to the study there’s a difference in WTW emissions between B2C and P2P car-sharing since B2C fleets are more fuel-efficient and have a higher percentage of low or zero-emission vehicles. One aspect is that most vehicles in B2C car-sharing models are replaced more often than private vehicles.

Effects of Car Sharing at City Level

Clear differences in the results for individuals underline the importance of modeling at the city level and the effects of car sharing on facilitating local sustainability targets. Especially important is to understand how the overall mobility system is affected and what the trade-offs are between individual gains and losses. The authors point out that their results suggest that car-sharing helps to decrease GHG emissions, providing there are fewer people disposing of owned cars or delaying a purchase than individuals with car-free travel habits who gained access to a car through car sharing.

Limitations

The researchers emphasize that this study is limited to only direct effects, namely GHG emissions, related to use. Other environmental effects should also be considered, along with the indirect effects of shared mobility and changes in consumption brought about by additional income or savings generated through the use of shared mobility. Capturing these would enable further understanding of how different modalities of shared mobility (B2C and P2P) translate into sustainability outcomes of personal mobility.

Conclusions

This study identified that, at the individual level, the use of car-sharing has various consequences for transport emissions. Previous car owners engaging with car-sharing tend to travel less and use low-emission transport modes, which results in lower GHG emissions. Car-free individuals, on the other hand, may travel more and use more emission-intensive transport modalities than before, which leads to the opposite effect. Emissions savings when individuals migrate to less emission-intensive travel habits and reduce travel distances seem to be more significant than the emissions increase of those whose travel distances increase due to the availability of car-sharing options. Depending on the characteristics of the shared fleets, the emissions will vary, with B2C fleets tending to have lower emissions per passenger-km than P2P.

The results at the city level suggest that a greater reduction in emissions can be achieved when green technology adoption (e.g., more fuel-efficient cars in sharing systems) is combined with behavioral changes (e.g., disposal of cars and more use of public transport), rather than implementing one of them. Such strategies can be enabled through appropriate environmental policies.

The various effects of car-sharing at the individual level must be considered when city governments are designing transport policies. Policies that focus on restricting parking in the city stimulate alternatives to vehicle ownership or delay purchase. Such policies would facilitate the use of public transport and shared mobility in a way that would reduce emissions in the city.

The study highlights that emissions from passenger transport can vary due to changes in individuals’ travel habits, different policies, or technological adaptation. When these happen simultaneously, the potential reductions of GHG emissions are the highest

Further research is needed to analyze the environmental effects of shared mobility, including assessments of other pollutants, material intensities, additional lifecycle stages, and the use of space. One important aspect to consider is the indirect effects of sharing, such as the impacts from changes in disposable income and re-spending. Other areas to be explored are the attributes of different business models in shaping user behaviour and the characteristics of the shared assets.